? What Jazz Music Selection are you Listening to in the Now? | Analog, Digital ??????

- Thread starter NorthStar

- Start date

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hey, jazz heads!! I'm sending out a survey that aims to measure listeners' responses to AI-generated jazz vs. human-composed jazz. I'd love to have some serious jazz fans take the survey and collect more data. Here's the link: https://forms.gle/mouyC8Zd8vj4qg646

And please don't forget to fill out the exit form linked upon completion! Thanks so much!

And please don't forget to fill out the exit form linked upon completion! Thanks so much!

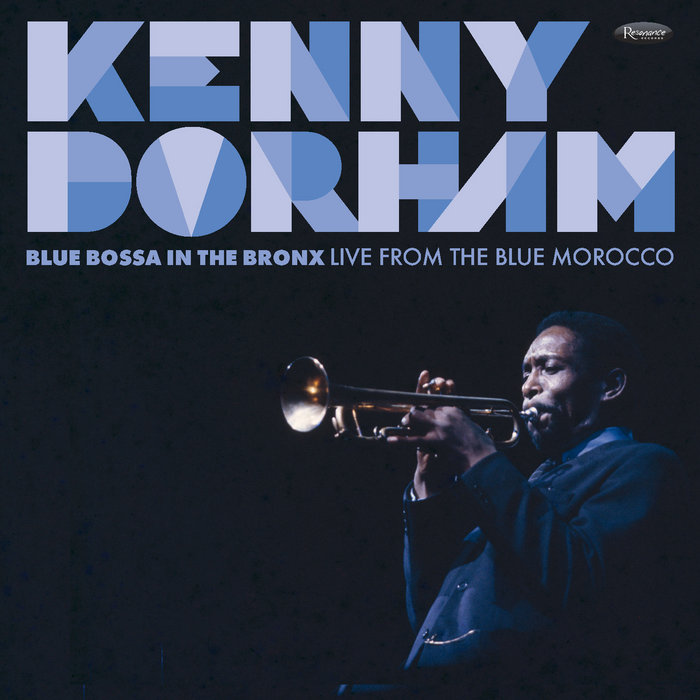

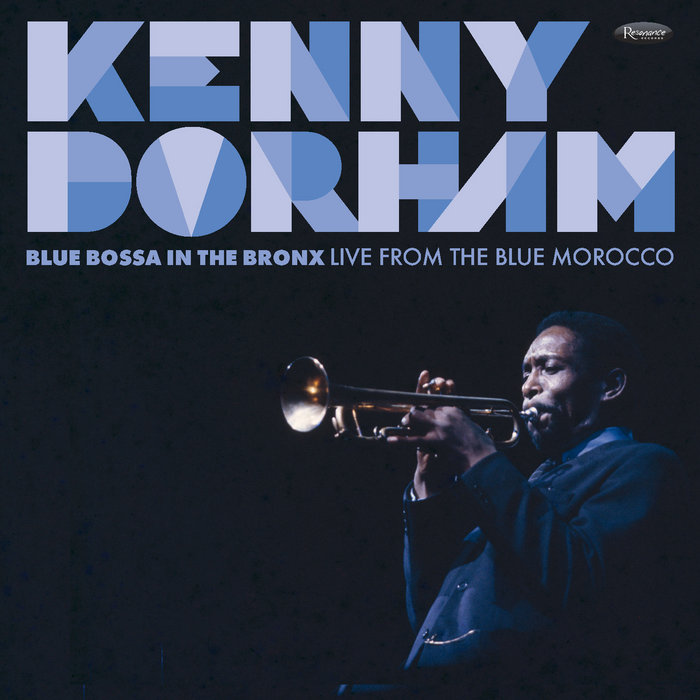

Three new releases from Resonance records (that I just purchased) and are worth checking out:

kennydorhamlive.bandcamp.com

kennydorhamlive.bandcamp.com

charlesmingusmusic.bandcamp.com

charlesmingusmusic.bandcamp.com

They are all previously unissued.

They can be sampled on Qobuz.

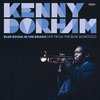

Blue Bossa In The Bronx: Live from the Blue Morocco, by Kenny Dorham

7 track album

kennydorhamlive.bandcamp.com

kennydorhamlive.bandcamp.com

In Argentina: The Buenos Aires Concerts, by Charles Mingus

13 track album

charlesmingusmusic.bandcamp.com

charlesmingusmusic.bandcamp.com

They are all previously unissued.

They can be sampled on Qobuz.

Not interested in listening to any AI-generated jazz, ever. Art is created by humans, period, and I have been fortunate to hear many of the jazz greats perform in person.Hey, jazz heads!! I'm sending out a survey that aims to measure listeners' responses to AI-generated jazz vs. human-composed jazz. I'd love to have some serious jazz fans take the survey and collect more data. Here's the link: https://forms.gle/mouyC8Zd8vj4qg646

And please don't forget to fill out the exit form linked upon completion! Thanks so much!

++1Not interested in listening to any AI-generated jazz, ever. Art is created by humans, period, ....

Of the problems with AI music, here are a few (IMHO):

A. No swing (in the rhythm)

B. No soul (genuine touch from the heart)

C. No human iddiocyhcricities (i.e. personality. Human recordings may even be fraught with haphazard mistakes, which then become important signatures of the performance/recording that we love)

Last edited:

++1

Of the problems with AI music, here are a few (IMHO):

A. No swing (in the rhythm)

B. No soul (genuine touch from the heart)

C. No human iddiocyhcricities (i.e. personality. Human recordings may even be fraught with haphazard mistakes, which then become important signatures of the performance/recording that we love)

You could say that about a lot of non-AI music!

I have.You could say that about a lot of non-AI music!

Illinois Jacquet

Illinois Jacquet And His Tenor-Sax

-Aladdin-

Illinois Jacquet And His Tenor-Sax

-Aladdin-

Gil Evans, Miles Davis Sketches of Spain, vinyl.

What a masterpiece.

What a masterpiece.

Liner Notes - Dan Morgenstern

This cooking album captures much of the spirit that used to be in residence at Count Basie's Lounge, one of Harlem's most pleasant and swinging music spots of the '50's and '60's.

The place was aptly named. Though the Count was much too busy leading a band to be on hand very often, the musical policy was almost always in keeping with what the Basie name has always stood for: Music you can tap your foot and shake your head to; music that swings and contains more than a hint of the blues.

When Basie did drop in, he'd usually hold court (though this may be the wrong expression to describe anything done by this most unassuming and natural of men) at a table in the far corner of the small, narrow room dominated by the long, gleaming bar on the left. The aisle separating it from the cluster of small tables along the right wall was narrow, and on a good night (few were bad in the club's halcyon days) the bar crowd, four or five deep, would spill over into the table area. The "bandstand" (there was no elevation) was simply a clearing between the tables with room for a set of drums, a tiny piano (it didn't have 88 keys -- just 66), some mikes and amps, and barely, the musicians.

Intimacy between artist and audience was the hallmark of the place, and it seeped into the grooves of this record. You can hear the appreciative grunts and groans and almost feel the presence of people having a good time to the music.

Until its final days, when new owners were attempting to save it through a big-name policy, the guiding spirit of Basie's was Clark Monroe, a man of infinite experience and wisdom when it came to dealing with the problems of operating a jazz establishment. He'd been a hoofer, was nick named "the dark Gable", and in the '30's and early 40's, when "Uptown" was synonymous with the best in jazz, ran one of the all-time greatest Harlem music spots, Monroe's Uptown House, at 7th Avenue and 134th Street -- just about a block away from where Basie's later stood.

Monroe's played host to such luminaries as Billie Holiday, Hot Lips Page, Roy Eldridge, Dizzy Gillespie, up-andcoming Charlie Parker, and any brave musician who felt he could hold his own in the after-hours jam sessions encouraged by the management. In 1943, Monroe moved downtown to 52nd Street to operate The Spotlight and become the first black owner (or at least manager) on that fabled block. Today, the site of Monroe's is occupied by Roy Campanella's liquor store.

Monroe knew how to run a place: Where to draw the line between good times and rowdiness, between toler. ance and anarchy. When someone crossed that line, he or she would shortly either be back on the right side of it or on the outside. Musicians were treated with respect, but they, too, had to observe that line.

There was no cover at Basie's, no minimum at the bar and a negligible one at tables. A bottle of cold beer, even well into the '60's, was just 50 cents at the bar, and there was good food (chicken and ribs) and friendly service at all times.

Among the "acts" that worked at Basie's, organists were often prominent (Wild Bill Davis, Shirley Scott, Marlowe Morris), with tenors running a close second and guitars third. The late Bobby Henderson was among the first incumbents and John Hammond supervised some memorable recording sessions involving Joe Williams, Sir Charles Thompson, Vic Dickenson and other notables on the premises. Lou Donaldson worked there, as did Illinois Jacquet. Mondays were jam session nights, presided over by the late Steve Pulliam, a capable trom- bonist who'd served many years with Buddy Johnson's band.

Joe Newman's fine little group, with occasional changes in personnel but none in musical outlook, was often heard at Basie's after he'd left the fold in the year this L.P. was recorded. Count has always remained on good terms with his alumni, and Joe for many years (1943-46 and 1952-61) was one of the most reliable and consistent men in the band.

Born in New Orleans, where his pianist father, Dwight Newman, for years led the Creole Serenaders at the famous Absinthe House, Joe started on drums, then switched to tenor sax, and at 10 decided to settle on the trumpet. On scholarship at Alabama State Teacher's College, he was in the 'Bama State Collegians when Lionel Hampton heard and hired him in 1941. Joe was 19 then, and hasn't looked back since.

After the stints with Hamp and Basie, Joe tried small group jump and bop with Illinois Jacquet and J. C. Heard, then made his nearly 10-year return engagement with Count, during which he also did a great deal of recording on his own, both as leader and featured sideman.

After leaving Basie, Joe settled in New York and became one of that competitive city's most steadily employed musicians, functioning in all sorts of situations calling for the qualities of technical command of the horn, improvisational prowess, consistency of execution, and quick grasp of scores and/or instructions. In short, he joined the professional elite.

Unlike some members of that elite, Joe has never lost his joy for making good music, nor has his own turn of fortune made him lose sight of the problems of the music community. With his wife, Rigmore, who also loves music, Joe founded and is president of Jazz Interactions, an organization dedicated to the furtherance and dissemination of jazz. JI has carried out some of the most effective educational programs involving the music, from in-school lecture-concerts to workshop projects for young musicians, and also sponsors free concerts, runs showcase presentations and lecture series, etc.

Joe's front line sidekick on this date, Oliver Nelson, has also come a long way since first hitting the Apple around 1958, after journeyman years in his native St. Louis and on the road. For a while, he studied taxidermy, but he eventually made his mark as a composer and arranger. Now, he is mainly scoring for films and TV, but hasn't lost touch with the jazz world.

As a player, though noted more for his work on alto and soprano than on the tenor, Nelson here proves himself fluent and articulate. But the solo spotlight throughout is where it belongs: On Joe Newman.

The rhythm department is in good hands. Lloyd Mayers, a product of New York's famed High School of Performing Arts (and Manhattan College), was a full-fledged violinist before turning to piano. Best known for a stint with the memorable Eddie Lockjaw Davis-Johnny Griffin group, he's also worked with Eddie Vinson, Dinah Washington, Nancy Wilson, and most recently, as pianist with the Duke Ellington Orchestra led by Mercer Ellington.

Bassist Art Davis made a name for himself through work with Max Roach, Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane, with whom he played after studies at the Juilliard School and Manhattan School of Music. Accomplished in all branches of music, he became submerged in studio work from the mid-'60's on, but surfaced again in the more advanced jazz circles of Manhattan in the early '70's.

Drummer Ed Shaughnessy's list of credentials is longer than our space. Suffice it to say that this product of Jersey City began his career as a protege of the immortal Big Sid Catlett, paid early dues with Lucky Millinder, Benny Goodman and George Shearing, has worked in every context imaginable (including lots of recording work with Count Basie), is at this writing the drummer in the Tonight Show Orchestra, and in late '74 formed a 17-piece band, Energy Force. He's got plenty of that, as he demonstrates here.

No extensive musical analysis is needed to enjoy this album. Caravan, the Ellington-Tizol classic, is given a most lively rendition, with Joe and Mayers outstanding, the latter in a Horace Silver bag.

Love Is Here, one of George Gershwin's last (and finest) tunes, is a Newman feature, all his excepting a brief bass interlude. It's top drawer Joe, and so is Someone To Love, Percy Mayfield's blue classic. It has the message, and you hear how Joe puts it across. Midgets was one of Joe's niftiest contributions to the Basie book. A fast, happy blues with a catchy stop-time device, it features all hands in fine form and cooks from start to finish. Dig the fours by the horns with Shaughnessy, who really goes to work here. The evergreen Dolphin Street opens a la Miles Davis (who put it on the jazz map via Cannonball Adderley's coat-pulling) and remains in that groove. Joe, with Harmon mute, is again the main contributor. Wednesday's Blues gets that down home feeling so appropriate to Basie's Lounge. Joe settles in (note the "chicken" sounds with which he begins his "strolling" choruses -- piano laying out) and really stretches out. Nelson pays tribute to Night Train, combining R&B touches with some freeform gyrations in a unique blend. The Joe re-enters and brings the mellow sermon to a rousing conclusion.

Live at Basie's indeed! This is "lively" music, so crisply played and so well recorded that it sits you right down in the middle of the Uptown ambiance of 1961 - - gone but not forgotten, and not the least bit dated, either.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 10

- Views

- 396

- Replies

- 3

- Views

- 391

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 199

- Replies

- 8

- Views

- 414

| Steve Williams Site Founder | Site Owner | Administrator | Ron Resnick Site Owner | Administrator | Julian (The Fixer) Website Build | Marketing Managersing |