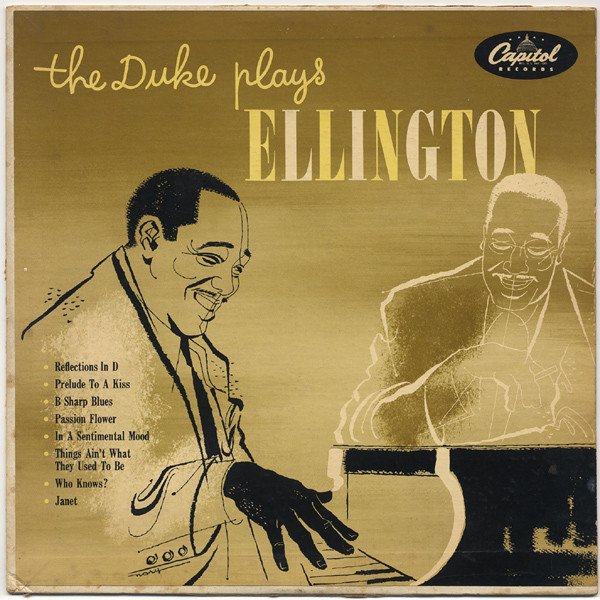

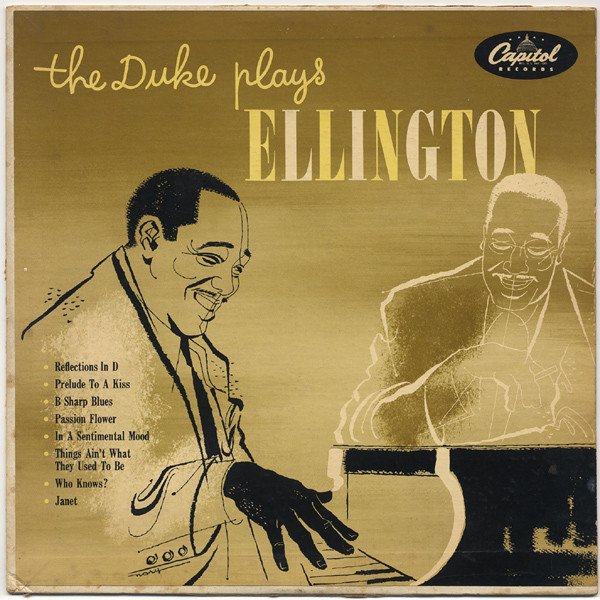

An Ellington album that I regularly come back to is "The Duke Plays Ellington", also issued as "Piano Reflections".

Here is the original LP issued in 1954 (the recording sessions took place in April 1953):

https://archive.org/details/lp_the-duke-plays-ellington_duke-ellington

This is his first album featuring him on piano. He is accompanied by Butch Ballard on drums, and Wendell Marshall on bass.

It was re-issued in 1972 as "Piano Reflections":

https://www.discogs.com/release/3361850-Duke-Ellington-Piano-Reflections

"Piano Reflections" includes additional tracks from this session, and a second session, in December 1953, with Dave Black replacing Butch Ballard on drums.

The sound quality may be different from what we are used to hearing today in modern productions, but IMO is very good and reveals well the qualities of Ellington's piano playing. I have both a CD version and an original LP. I enjoy both, but the LP offers a little more "authenticity".

Eddie Lambert summarizes his thoughts as follows: "The 1953 piano solos for Capitol are of modest dimensions and demeanor, their considerable subtlety and depth apparent only to those who listen beneath the surface."

The late academic, author, Ellington "expert", and pianist

Mark Tucker explains in more detail

:

"...Backed by bassist Wendell Marshall and two different drummers—Butch Ballard in April and Dave Black in December—Ellington performed fourteen pieces, eight of them new. This burst of pianistic activity in the studio foreshadowed the 1960s, when Ellington would make more recordings with bass and with trio (including the notorious Money Jungle session with Charles Mingus and Max Roach in 1962), and when he would begin to give public solo piano recitals.

Out on the West Coast in the spring of 1953, Ellington’s orchestra made its first recordings for Capitol on April 6, in a session that produced a piece called

Satin Doll. A week later Ellington returned to the studio with Marshall and Ballard, leading off with three new piano compositions:

Who Knows?,

Retrospection, and

B Sharp Blues.

The main theme of

Who Knows? displays Ellington’s chromatic bent (which he once traced to the noted arranger Will Vodery), while the bridge features left-hand voicings associated with Willie ‘the Lion’ (cf. Morning Air, recorded in 1939). Ellington’s two solo choruses show his mastery of register, as he gracefully executes large leaps and now and then cascades down the keyboard with runs of startling intensity. The mood quiets down with

Retrospection, a sober meditation with harmonies that echo the Victorian parlor songs and hymns of Ellington’s youth. The performance of

B Sharp Blues is as witty as its tongue-in-cheek title, with Ellington’s sudden surprising dissonances, his sly allusions to a theme from Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue (1937), and his pared-to-the-bone lines which, in the hands of a lesser pianist, might sound like clichés. Ellington’s transforming touch, however, gives them a brittle, modern quality that may remind some listeners of Thelonious Monk.

To round out the session Ellington turned to two pieces that dated from the previous decade. Billy Strayhorn’s

Passion Flower, first recorded by Johnny Hodges and a small group in 1941, had become one of the alto saxophonist’s primary vehicles. In 1953 it was still in the Ellington band’s repertory even though Hodges had departed two years earlier (only to rejoin in 1955). Ellington’s interpretation manages to suggest a sense of erotic anticipation even if something of Hodges’s warmth and sensuality are missed. On

Dancers in Love, however, from the 1944 Perfume Suite, Ellington captures the youthful ebullience’ of the original. In his memoirs, he wrote that the piece represented ‘naiveté, a stomp for beginners,’ and the deliberately basic chord sequence following the chromatic first theme underscores the dancers’ adolescent infatuation.

The next day, April 14, Ellington began with two haunting compositions,

Reflections in D and

Melancholia, accompanied only by Marshall on bowed bass. Both pieces point to the difficulty—futility even—of trying to categorize Ellington’s music, for while they draw upon the harmonic vocabulary of jazz, their rhythmic freedom and ethos seem to belong to another world altogether: an idealized realm of memory, nostalgia, and spirituality more characteristic of the nineteenth century than the twentieth. In the context of Ellington’s overall output, these two works—together with the previous day’s Retrospection— form a link between earlier ‘mood pieces’ (Awful Sad, Mood Indigo, Solitude) and the sacred music of the ‘60s (Meditation, Heaven, T.G.T.T.).

Framed by a lovely bell-like figure,

Reflections in D has the private quality of a prayer — the listener almost feels like an eavesdropper on an interior monologue, yet privileged to be allowed so near. For

Melancholia Ellington drops down a half-step to D-flat for a gentle piece edged in sorrow. (Recently the trumpeter Wynton Marsalis has been attracted to Melancholia’s special qualities, recording it on two of his albums.)

For the next four offerings Ellington dipped again into his repertory of standards.

Prelude to a Kiss, first recorded in 1938, was another Johnny Hodges feature. Unlike the sustained melody notes of

Passion Flower, however, its moving chromatic lines adapt easily to keyboard treatment. Ellington’s tone is warm and rich; he sticks close to the theme throughout, as though it were too lovely to let go. This performance could serve as a study for all pianists in how to balance chords and produce a full-bodied sound without exerting undue pressure. In the early days Ellington emulated Lucky Roberts and some of the ragtime pianists by throwing his hands high off the keyboard and, accordingly, producing a more percussive sound. But by 1953 he had settled down a bit, and film footage from the later years shows him keeping his hands quite close to the keys, his wrists supple, and his fingers slightly curved in ‘classical’ position.

If

Prelude to a Kiss is a study in tone,

In a Sentimental Mood demonstrates Ellington’s inimitable touch. Especially impressive is the way he shades each note of the theme by either quick releases, half-pedaling, or finger legato. The constant variety of attacks and releases makes the familiar theme fresh. The trio settles into a relaxed blues groove on

Things Ain’t What They Used to Be, demonstrating close ensemble interplay with Marshall’s fills, Ballard’s punctuating accents, and in the second chorus, Ellington’s tremolo response to a drum roll. This performance reveals how Ellington preferred building blues choruses out of short motives rather than soloing on the changes. A good example is in the fourth chorus, when Ellington ‘worries’ a two-note figure spaced over an octave apart. Ellington probably derived this practice from the ragtime and stride players, for whom melodic elaboration and embellishment took precedence over harmony-generated improvisation.

All Too Soon, first recorded in 1940 as a feature for trombonist Lawrence Brown and tenor saxophonist Ben Webster, later performed as a song with Carl Sigman’s lyrics, is one of Ellington’s most inspired melodies. Even without a text it tells a story through a series of connected, unfolding statements. Although the piece follows the conventional AABA pop song plan, Ellington wrote a varied, summary-like phrase for the last A section which enhances the narrative quality (i.e., the song’s bridge leads not back to the beginning but to somewhere new). As with the preceding three standards, Ellington treats

All Too Soon not as a vehicle for improvisation but as an affirmation of melody.

Janet is perhaps the most unusual piece Ellington recorded on these two days. Apparently named after the daughter of a friend, it was performed rarely by Ellington (he did include it on his first public piano recital, 14 January 1962, at the Museum of Modern Art). What’s different is the form: a slow, moody middle flanked by two lively outer sections (turning inside out the scheme found in

The Clothed Woman of 1947.) Perhaps the contrasts reflect Janet’s different traits or moods. Ellington often cited various stimuli that inspired his compositions—natural phenomena, places, people, states of feeling, even trains (both express and local). In this case, the three-part

Janet succeeds as a miniature tone portrait while the identity of its subject remains obscure."

Enjoy!